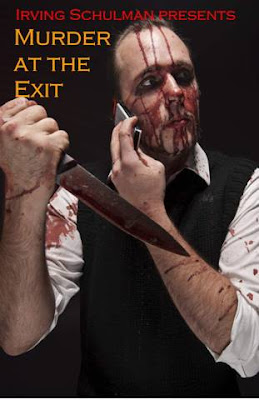

My review of Murder at the Exit has been controversial. In the first day of being published, readers have said it’s “hilarious” and “terrible”; one said he “loved” it.

My writing was inspired by this film review, by Chris

Packham of the Village Voice. Earlier

this week, my editor sent it to me as an example of "making a review about something more.” Then just today, in a show of unabashed nepotism, SF Weekly awarded it “the best movie review of 2012.” (The two papers are owned by the same

company, Village Voice Media.)

The first time I read the review, I felt, in a word,

sucker-punched. It surprised me, and it made me feel guilty for

most of the pans I’ve written — a lot to accomplish in just 265 words.

Packham is at once extremely critical and extremely

forgiving, which feels alternately like a genius balancing act and a cop-out.

It’s an unusual approach, and it, too, has generated controversy, much more

than my review has. I can only imagine what it’s like to get 37 comments on a

review, and I probably don’t want to.

The surprise I felt reading Packham’s piece stuck with me,

and when last week I saw Murder at the

Exit, by Catchy Name Theatre Co. and the Unknown Players, I decided a similar approach might suit my own review. The

result is an article that talks relatively little about theater and much more

about my theatergoing.

Because my review is so critical, one of Murder’s artists and I got into a discussion about harsh criticism —

a perennial topic on this site, but also one that’s been getting a lot of press

lately. The ruckus started with Jacob Silverman's "Against Enthusiasm," in Slate. He argues:

If you spend time in the literary Twitter- or blogospheres, you'll be positively besieged by amiability, by a relentless enthusiasm that might have you believing that all new books are wonderful and that every writer is every other writer's biggest fan. It's not only shallow, it's untrue, and it's having a chilling effect on literary culture, creating an environment where writers are vaunted for their personal biographies or their online followings rather than for their work on the page... Reviewers shouldn't be recommendation machines, yet we have settled for that role, in part because the solicitous communalism of Twitter encourages it. Our virtue over the algorithms of Amazon and Barnes & Noble, and the amateurism (some of it quite good and useful) of sites like GoodReads, is that we are professionals with shaded, informed opinions. We are paid to be skeptical, even pugilistic, so that our enthusiasms count for more when they’re well earned.

His point is well-taken, but his gripe seems to be more with Twitter than with criticism that's allotted more than 140 characters. Then Dwight Garner corroborated Silverman's point, addressing the wimpy state of criticism as a whole with "A Critic's Case for Critics Who Are Actually Critical," in the Times. But he defines "critical" more inclusively than Silverman does:

The sad truth about the book world is that it doesn’t need more yes-saying novelists and certainly no more yes-saying critics. We are drowning in them. What we need more of, now that newspaper book sections are shrinking and vanishing like glaciers, are excellent and authoritative and punishing critics — perceptive enough to single out the voices that matter for legitimate praise, abusive enough to remind us that not everyone gets, or deserves, a gold star... Criticism doesn’t mean delivering petty, ill-tempered Simon Cowell-like put-downs. It doesn’t necessarily mean heaping scorn. It means making fine distinctions. It means talking about ideas, aesthetics and morality as if these things matter (and they do). It’s at base an act of love. Our critical faculties are what make us human.

Then just today,

Richard Brody of the New Yorker retaliated with "How To Be A Critic":

[Silverman's] very title, “Against Enthusiasm,” rankles. Enthusiasm should be more or less the only thing that gets a critic out of bed in the morning, except in the case of ghouls who are aroused by the taste of blood.

For him, Garner, with his use of words like "punishing" and "abusive"

sounds like the strap-wielding father who tells his children that they’re being beaten for their own good, and that’s the institutional menace of criticism—the sense that the critic represents a kind of order or rule to which the unruly artist needs to be recalled.

Brody doesn't condemn negative reviews, but he offers a word of caution:

It’s naïve to think that negative reviews have no effect on artists’ psyches or careers, and critics should consider what it takes to recover from wounds before inflicting them.

None of these thoughts are new. In 1950, Kenneth Tynan described prevailing English theater criticism as “bled into weakness and deformity. It has lost the almost moral intensity it used to boast.”

At best, the critics “address themselves…to the suburban fortresses

of semi-culture. At worst, they shape themselves to please it.” Their style,

what’s more, had “many more semicolons than full stops, many more puns than

points, and as in Beddoes’s poem, many more shadows than men.” Nor was he the first (he was just the best!); Bernard Shaw made similar

exhortations 50 years prior.

I’ve only been writing theater criticism for a few years,

but in just that span I've seen many iterations of the same two questions: When does criticism go too far? When does it fail to go far enough? We

don’t come up with many new responses, but every time I read the latest such essay I agree with it — even if I recently agreed with an essay arguing the opposite. “Yes,

criticism is too snarky, too harsh,” I’ll think; then, when the next article comes along, I'll say, “Criticism isn’t honest enough; everyone’s pulling his or her punches.” I like to think that my seeming ambivalence shows a larger point: that criticism matters, that

it’s a vital part of the process of making professional art — often the final step in

the process. It matters in the way art matters, so we critics need to constantly

interrogate ourselves. And we have this conversation over and over again

because it’s the best way to do so; one new well-wrought phrasing of one of

these well-worn ideas can and should unsettle your critical practice. Just

because you answer the questions one way at one point, any review you write —

indeed, any sentence — could reveal that your old answers are no longer the

best answers. If that never happens for you, if you never feel that danger when you

write, then you, my friend, might well be a hardened hack. (And I feel that way all too often!) "

From the three articles mentioned above, these passages, from

Brody's piece, resonate most with me:

Criticism is a damned and doomed activity, because critics have (or should have) a sick feeling of bad faith every time they lift the pen or strike the keyboard.

A review, however rapidly composed, may well have an aphoristic brilliance or a mercurial insight that’s missing from a work under consideration (at its best, criticism is aesthetic philosophy practiced in a periodical or is in itself a literary performance). But even in the midst of such inspirations, the critic ought to harbor the shadow of a doubt whether these flourishes are conceived in the spirit of the art or at its expense.

Criticism, if it’s worth anything at all, is, first of all, self-criticism.

There you have it, friends, the real reason why Lily’s a

critic: It's an opportunity to live fully in guilt and doubt in the professional

world!

In all seriousness, though, Brody doesn’t paint the full

picture. Critical doubt induces dread (and occasionally paralysis), but the danger also thrills. It's tremendously exciting to cast to the wind your notions of what theater should be, what criticism should be, and dive recklessly into the unknown. That's what I felt, in some small way, when I reviewed Murder at the Exit. I hope some other show does this to me sometime soon (but maybe not tomorrow).

Murder at the Exit continues through Aug. 25; info here.

Murder at the Exit continues through Aug. 25; info here.

Well, you're just a puddin' cup. Thanks for the kind words. A lot of people in the comments misunderstood my point. I think the perception is that I was refusing to criticize "Knight Knight," despite the fact that I did, and pretty negatively. I was trying to make a distinction between being critical and being a deliberately hurtful douchebag. Halfway through the film, I realized that making fun of it would be like mocking a child's stupid macaroni art or something. I want to be honest -- even devastatingly honest -- but I don't want to be a bully.

ReplyDeleteI reviewed a terrible film in the same issue called "The Revenant," and made no attempt at kindness toward its creators because the valence of the film was overwhelmingly mean-spirited and reactionary. I felt that it was deliberately punching down at poor people and ethnic minorities in the name of entertainment. The point being that I don't think anybody can accuse me of being a dancing monkey. No offense intended toward cute monkeys, particularly the ones dressed up like little bellhops.

I almost wrote a paragraph about how the "good intentions" comment in your review was probably a lot more important than people were acknowledging -- not that there isn't a lot of bad artwork with good intentions out there, but a critic certainly couldn't take an approach like this every time s/he wanted to be critical, as it would lose all its surprise and force. I could tell you wouldn't have written this about any ol' bad movie!

ReplyDeleteAlso: I am so honoured to be a puddin' cup.

Ok, last thing and I swear I'm done with Knight Knight. Leveling brains and irony against bad art is almost a reflex now, it's expected and sometimes important. But because irony has exclusively negative polarization, I think it should be reserved for works with negative intentions or motivations rather than taking a bead on the artless work of amateur enthusiasts, because come on. I've certainly spent time writing mean things on the Internet, and there aren't many of those pieces I'm comfortable looking back on. Anyway, I've been thinking about this a lot lately, and I'm glad you gave the opening to talk about it. Also: Nice to meet you, new internet pal.

DeleteNice to meet you, too! Excited to read your next review.

ReplyDelete